INTERVIEW

Ana Dumitrescu interviewed by Jean-Pierre Carrier *Can you introduce us to your film, «Licu, a Romanian story» ?

“Licu,” my latest feature documentary, happens to be my first Romanian movie and the first film I have made with my film-production company “Jules et Films.”

I am French of Romanian origin and I have never lived in Romania beforehand, with the exception of a two-year photographic interlude I spent there since 2007 to 2009. I used to enjoy listening to my grandmother telling me those old-time stories. The Romania I have known is, in fact, the Romania I have learnt about from my father’s and grandmother’s memories. In a way, this movie is a reflection of my own memories as a child when I was listening to those stories about a world I had never known. A movie made of memories. It is about a world depicted from my personal perspective through the eyes of those who had lived it in their own way. I have always enjoyed listening to the others telling me their stories and browsing through old-epoch photos. For me, this film is somehow like Proust’s Madeleine.

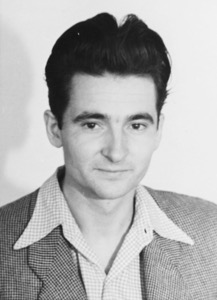

Coming back to the film - it is the story of a life, a 92-year-old man’s life who tells us his little story within the big story. It is like an ode to time passing-by, to his life, to our lives. It is a movie filled with dialogue, and seemingly time is flowing slowly. This is the paradox that ultimately reflects life itself. Life passes too fast, gets occupied with lots of events and yet time seems suspended or in slow motion.

Producer’s secret. I would just say that a part of his story is a part of me as well.

What is the part of yourself in the character you are portraying?

My films are subjective. They necessarily pass through the filter of my own vision. “Licu,” I would say is a double subjective film as it passes first through the filter of the character’s memories and then through my own filter. For instance, the film takes place behind closed-doors in the character’s home. This was a fully assumed choice. I could have filmed him while doing grocery shopping or driving his car (he was still driving at that time) but I decided to unfold the action behind ‘closed-doors’, making it in its turn a character as well. This generation of a “certain age” or let’s put it as the older-aged persons, did not seem to enjoy going out that much. For instance, I never managed to have my grandmother accept my invitations to dine out together; maybe with one exception, once only, when we went to the mountains together. Thus, my own memories are to a certain extent behind closed-doors. And here’s again Proust’s Madeleine, which we were talking about earlier. Memories are like some sort of confession. It’s an intimate moment.

While editing the film, I chose to keep certain sequences and remove others, as it was not my intention to make a ‘personal-themed film’, but a universal one. I put the emphasis on the elements that can be cross-referenced with History.

Can your film be rated as a «historical» film?

This nationalistic romanticism felt for that period is a common feature within Romania’s present social context. The era before the Second World War is perceived like a sort of a mythical Eden. The truth is certainly somehow more mitigated. However we should not overlook that Licu was born in a middle-class family. And the pre-war era had been prosperous for the middle-class. I would also mention that ultimately, in spite of the common belief, the communism was not as difficult a period as one might have imagined. Of course, there were the purges during the 50s which was undeniably a terrible period having struck mostly the intellectuals. Later on, the middle class which he belonged to as an engineer, enjoyed privileged positions. The engineers were regarded as assets to the government for their input in the modernization projects. In conclusion, nothing is really black or white. Everyone experienced and lived the pre-war and the communist periods differently according to their status in the society at that time. Thus, this movie without being a historical film in the strict sense of the term, exposes the character’s views which do match the views of many Romanians today. It is therefore a case study, yet a representative film.

Before turning to the documentary cinema, you used to work as a photojournalist. Can you explain this turning point? Is there any trace of this first profession left in your present work as a filmmaker? Are you still a photographer?

I started with documentary photography on various subjects such as homosexuality in Romania or the deportation of Roma during the war. I have always enjoyed dealing with my subjects in depth, taking the time to photograph and getting to know the people; therefore, we cannot really talk about a transition to documentary but rather a change of support, from photography to the «animated» image. Technological changes have facilitated this transition (like the filming camera). Today I hardly do any photos, but photography serves me on a daily basis. I have evolved to more advanced techniques, and a particular attention is paid to the light. I tend to make each shot look like a photograph.

Do you consider yourself an «engaged» filmmaker?

I consider myself a humanist. I really love the others, and that’s why I enjoy filming them. I could not film or make a movie about people or ideas I dislike, or do not have respect for. All my films have one thing in common: they talk about tolerance, respect, human values. Cinema is a powerful engine involved in the progress of society. It deals with a variety of topics casting different views and perspectives on situations often ignored. So, yes, like many other filmmakers, I am dedicated to our common humanistic values. Isn’t this the very motivation that stands at the core of why we are making films?